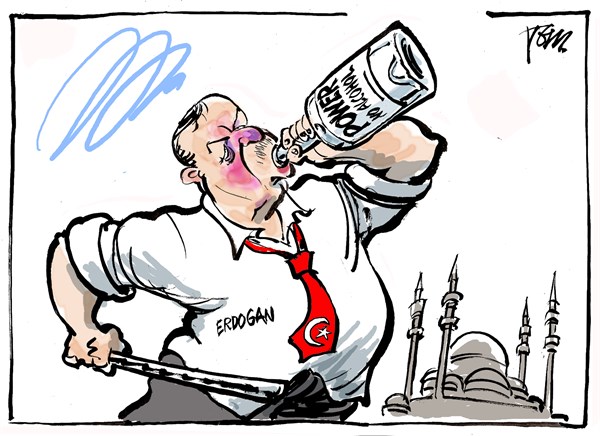

Here we go again. Another Dictator want to ban social media, so that he can have total control and probably have some unwanted elements disappear!

Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan said yesterday Turkey could ban Facebook and YouTube after local elections on 30 March, saying they have been “abused” by his political enemies.

Erdogan is locked in a power struggle with US-based Turkish Muslim cleric Fethullah Gülen, a former ally who he says is behind a stream of “fabricated” audio recordings posted on the Internet purportedly revealing graft in his inner circle.

“We are determined on this subject. We will not leave this nation at the mercy of YouTube and Facebook,” Erdogan said in an interview late on Thursday with the Turkish broadcaster ATV. “We will take the necessary steps in the strongest way.”

Asked if the possible barring of these sites was included in planned measures, he said: “Included.”

In August 2008, when the Tunisian government shut down Twitter for 16 days, it was confronted with a threat by cyber activists to close their internet accounts. The regime was forced to back down. Instead, says Koubaa, the Tunisian authorities attempted to harass those posting on Facebook. This left a peculiar loophole that persisted until December 2008, when the regime finally launched a full-scale attack against Facebook. This in in a country that already tortured and imprisoned bloggers, and where the country's internet censors at the Ministry of the Interior were nicknamed "Amar 404" after the 404 error message that appeared when a page was blocked. If Twitter had negligible influence on events in Tunisia, the same could not be said for Egypt. A far more mature and extensive social media environment played a crucial role in organising the uprising against Mubarak, whose government responded by ordering mobile service providers to send text messages rallying his supporters – a trick that has been replicated by Muammar Gaddafi. In Egypt, details of demonstrations were circulated by both Facebook and Twitter and the activists' 12-page guide to confronting the regime was distributed by email. Then, the Mubarak regime – like Ben Ali's before it – pulled the plug on the country's internet services and 3G network. What social media was replaced by then – oddly enough – was the analogue equivalent of Twitter: Handheld signs held aloft at demonstrations saying where and when people should gather the next day. Iran’s Culture Minister Ali Jannati joined a growing number of high-profile government figures last year, calling for Iran to lift its ban on Facebook and Twitter — imposed after the so-called Twitter revolution of 2009, in which social media were widely used to foment anti-government unrest.

Turkey on its way to a people’s revolution?…as we know the military, the warrantor of Kemalism, had its teeth pulled by Erdogan.

Erdogan says the release of his purported conversations is part of a campaign to discredit him and wreck his government, which has presided over more than a decade of strong economic growth and rising living standards in NATO member Turkey.

Gülen denies any involvement in the recordings and rejects allegations that he is using a network of protégés to try to influence politics in Turkey.

Five more recordings have appeared on YouTube this week, part of what Erdogan sees as a campaign to sully his ruling centre-right AK Party before the 30 March municipal elections and a presidential poll due later this year.

In the latest recording, released on YouTube late on Thursday, Erdogan is purportedly heard suggesting the proprietor of Milliyet newspaper sack two journalists responsible for a front page story about Kurdish peace talk efforts.

Erdogan has signaled that a criminal investigation could be launched against Gülen's Hizmet movement.

Asked on Thursday night whether Turkey could seek an Interpol red notice for the extradition of Gülen from the United States, Erdogan said: “Why not?”

Muhammed Fethullah Gülen (born 27 April 1941) is a Turkish preacher, former imam, writer, Islamic opinion leader, and the founder of the Gülen movement (aka Hizmet). He currently lives in a self-imposed exile in Saylorsburg, PA/USA. Gülen teaches an Anatolian (Hanafi) version of Islam, deriving from Sunni Muslim scholar Said Nursî's teachings. Gülen has stated that he believes in science, interfaith dialogue among the People of the Book, and multi-party democracy. He has initiated such dialogue with the Vatican and some Jewish organisations.

Gülen is actively involved in the societal debate concerning the future of the Turkish state, and Islam in the modern world. He has been described in the English-language media as “one of the world's most important Muslim figures.” However, his Gülen movement has been described as “having the characteristics of a cult” and its secretiveness and influence in Turkish politics likened to “an Islamic Opus Dei.” In the Turkish context, Gülen appears as a religious conservative.

Gülen has criticised secularism in Turkey as “reductionist materialism.” However, he has in the past said that a secular approach that is “not anti-religious” and “allows for freedom of religion and belief, is compatible with Islam.” According to one Gülen press release, in democratic-secular countries, 95% of Islamic principles are permissible and practically feasible, and there is no problem with them. The remaining 5% “are not worth fighting for.”

Gülen's views on women are “progressive” but “modern professional women in Turkey still find his ideas far from acceptable.” Gülen says the coming of Islam saved women, who “were absolutely not confined to their home and ... never oppressed” in the early years of the religion. He feels that western-style feminism, however, is “doomed to imbalance like all other reactionary movements ... being full of hatred towards men.” However, Gülen's views are vulnerable to the charge of misogyny. As noted by Berna Turam, Gülen has argued: “the man is used to more demanding jobs ... but a woman must be excluded during certain days during the month. After giving birth, she sometimes cannot be active for two months. She cannot take part in different segments of the society all the time. She cannot travel without her husband, father, or brother.”

Gülen has condemned terrorism. He warns against the phenomenon of arbitrary violence and aggression against civilians and said that it “has no place in Islam.” He wrote a condemnation article in the Washington Post on 12 September 2001, and stated that “a Muslim cannot be a terrorist, nor can a terrorist be a true Muslim.” Gülen lamented the “hijacking of Islam” by terrorists.

The Gülen movement has millions of followers in Turkey, as well as many more abroad. Beyond the schools established by Gülen's followers, it is believed that many Gülenists hold positions of power in Turkey's police forces and judiciary. Turkish and foreign analysts believe Gülen also has sympathisers in the Turkish parliament and that his movement controls the widely-read Islamic conservative Zaman newspaper, the private Bank Asya bank, the Samanyolu TV television station, and many other media and business organizations, including the Turkish Confederation of Businessmen and Industrialists (TUSKON). In March 2011, the Turkish government arrested the investigative journalist Ahmet Sik and seized and banned his book The Imam's Army, the culmination of Sik's investigation into Gülen and the Gülen movement. In 2005, a man affiliated with the Gülen movement approached then-US Ambassador to Turkey Eric S. Edelman during a party in Istanbul and handed him an envelope containing a document supposedly detailing plans for an imminent coup against the government by the Turkish military. However, the documents were soon found to be forgeries. Gülen affiliates claim the movement is “civic” in nature and that it does not have political aspirations.

Despite Gülen's and his followers' claims that the organisation is non-political in nature, analysts believe that a number of corruption-related arrests made against allies of Erdogan reflect a growing political power struggle between Gülen and the still PM. These arrests led to the 2013 corruption scandal in Turkey, which the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP)'s supporters (along with Erdogan himself) and the opposition parties alike have said was choreographed by Gülen after Erdogan's government came to the decision early in December 2013 to shut down many of his movement's private Islamic schools in Turkey. The Erdogan government has said that the corruption investigation and comments by Gülen are the long term political agenda of Gülen's movement to infiltrate security, intelligence, and justice institutions of the Turkish state, a charge almost identical to the charges against Gülen by the Chief Prosecutor of the Republic of Turkey in his trial in 2000 before Erdogan's party had come into power. Gülen had previously been tried in absentia in 2000, and acquitted in 2008 under Erdogan's AKP government from these charges. In emailed comments to the Wall Street Journal in January 2014, Gülen said that “Turkish people ... are upset that in the last two years democratic progress is now being reversed,” but he denied being part of a plot to unseat the government. Later, in January 2014 in an interview with BBC World, Gülen said, “if I were to say anything to people I may say people should vote for those who are respectful to democracy, rule of law, who get on well with people. Telling or encouraging people to vote for a party would be an insult to peoples' intellect. Everybody very clearly sees what is going on.”

Discursive and organisational strategies of the Gülen movement

No comments:

Post a Comment